SPOILER WARNING: Watch the movie before you read this!

Fifteen years after its release, David Fincher’s film Fight Club, based on the novel by Chuck Palahniuk, is an excellent example of how modern storytellers can use a timeless mythological structure to explore contemporary social issues. The movie employs elements of the hero cycle to examine the social construction of gender identity as well as the existential emptiness that arises from a blind faith in consumerism and other secular alternatives to traditional religious values.

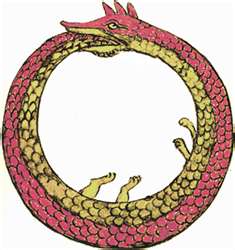

At its twisted heart, this postmodern odyssey is what mythologist Joseph Campbell called the monomyth, a universal narrative rooted in the collective unconscious and symbolizing psychological development, a process Carl Jung referred to as individuation. From all appearances, the ambiguously named protagonist should be content: he’s a college graduate with a well-paying white-collar gig and a lovely condo full of nice Scandinavian furniture, but he is far from satisfied. His adventure begins when his home is destroyed by a mysterious explosion, and he moves in with his new friend, Tyler Durden. Tyler is too good to be true. Archetypal companion and mentor rolled into one, he assists the protagonist across the threshold and initiates a quest for a more authentic life, providing philosophical guidance along the way.

What the protagonist wants to avoid is Marla Singer, the primary female presence in his life. Marla’s assertive, self-assured style brings out the main character’s insecurities. Tyler helps him channel this anxious energy into hyper-masculine practices that give him a new sense of confidence and self-worth. As Tyler’s nihilistic beliefs and violent rituals, which form the basis of Fight Club, escalate into a domestic terrorist organization called Project Mayhem, the protagonist finally confronts Tyler and comes face-to-face with a stunning fact that he’s hidden from himself. Tyler is actually his own dissociated persona, a fabricated alter ego who embodies everything the protagonist believes he wants to be. In reality, his mentor-companion is a shadowy trickster, a product of his own fragmented unconscious. In terms of Campbell’s monomyth, this is the hero’s apotheosis—the climactic confrontation with his own inner demons—and his ability to overcome and integrate the Tyler persona makes him worthy of his ultimate boon: the chance to have a mature relationship with a member of the opposite sex. Marla isn’t the antagonist his twisted psyche perceived her to be. Instead, she is, in Jungian terms, the object of his anima projection, the feminine side of the male psyche. Now that he’s overcome his shadow, the protagonist has the potential to gain a higher degree of self-mastery and have more mature relationships. Of course, he realizes this as skyscrapers topple—cue the Pixies and roll the credits.

On a fundamental level, Fight Club is a story as old as human history itself: a heroic quest that is metaphorical of both psychological development and successful social integration. On a more immediate level, though, the film functions as meta-commentary on individualism and the problematic task of having to construct a meaningful identity in contemporary American culture. For most of its history, after all, this country has been dominated by patriarchal, Christian values. Fathers were expected to provide for their wives and children, ruling over them like domestic gods. Over the last century or so, those expectations have radically changed, and Fight Club constantly questions the psychosocial impact of this paradigm shift.

Looking to cure his insomnia, the protagonist joins ‘Remaining Men Together,’ a support group for survivors of testicular cancer. Here, traditional notions of masculinity are inverted. These men openly share their feelings, weep, and hug. One member, Bob, has large breasts, an ironic side-effect of his steroid abuse. The surgery, which has anatomically emasculated them, symbolizes the effect feminism has had on the conventional definition of manhood. And then there’s Marla: her assertive personality clearly troubles the protagonist, which is why he invents a hyper-masculine alter ego in the first place. Through this persona, he voices an anti-feminist ideology: “We’re a generation of men raised by women. I’m wondering if another woman is what we need.” Tyler refers to himself and fellow Fight Club members as children—as “God’s unwanted children” and “the middle children of history.” According to his philosophy, empowered women have driven their men away, leaving their sons to be raised without proper male role models and thus little chance of becoming ‘real men.’

Looking to cure his insomnia, the protagonist joins ‘Remaining Men Together,’ a support group for survivors of testicular cancer. Here, traditional notions of masculinity are inverted. These men openly share their feelings, weep, and hug. One member, Bob, has large breasts, an ironic side-effect of his steroid abuse. The surgery, which has anatomically emasculated them, symbolizes the effect feminism has had on the conventional definition of manhood. And then there’s Marla: her assertive personality clearly troubles the protagonist, which is why he invents a hyper-masculine alter ego in the first place. Through this persona, he voices an anti-feminist ideology: “We’re a generation of men raised by women. I’m wondering if another woman is what we need.” Tyler refers to himself and fellow Fight Club members as children—as “God’s unwanted children” and “the middle children of history.” According to his philosophy, empowered women have driven their men away, leaving their sons to be raised without proper male role models and thus little chance of becoming ‘real men.’

The film also critiques the idea that consumerism can offer an adequate solution. While riding a bus, the protagonist and Tyler discuss a Calvin Klein underwear ad featuring a young, muscular model. When the protagonist asks if the image is manly, Tyler replies, “Self-improvement is masturbation. Now self-destruction.” His theory implies that media representations of masculinity only intensify the problem. The superficial ideal is difficult, if not impossible, to achieve, which actually serves corporate America’s agenda because men will keep buying more products in a futile attempt to fill the void. That is why Tyler preachers an anti-media, anti-consumerist position: “We were all raised to think we’d be celebrities and rock gods,” he says, “but we won’t, and we’re slowly waking up to that fact.”

The film’s examination of gender construction and consumerism ultimately converge on a deeper theme: the dramatic changes in America’s religious landscape. Until Marla’s arrives on the scene, the support groups provide a temporary cure for the protagonist’s insomnia, allowing him to find some degree of inner peace. It becomes clear, however, that the New Age pop-psychobabble is a superficial substitute for the existential stability traditional religious beliefs once provided. The meetings are actually held in churches, but rely on secularized language and practices, not scripture and liturgy. Nevertheless, Fincher suggests that piety still lingers in the background. At Remaining Men Together, when the protagonist is finally able to cry, choral music plays on the soundtrack, implying that, despite the secularized context, the weeping has a deeply spiritual quality, a connection reinforced by the main character’s use of evangelical terms to describe the experience. He says the groups make him feel “born again” and “resurrected.” The chemical burn scene connects this ambiguity and ambivalence back to the gender issue when Tyler says, “Our fathers were our models for God. If our fathers bailed, what does that say about God?” Tyler’s answer: “God does not like you. In all probability, he hates you.”

The film’s examination of gender construction and consumerism ultimately converge on a deeper theme: the dramatic changes in America’s religious landscape. Until Marla’s arrives on the scene, the support groups provide a temporary cure for the protagonist’s insomnia, allowing him to find some degree of inner peace. It becomes clear, however, that the New Age pop-psychobabble is a superficial substitute for the existential stability traditional religious beliefs once provided. The meetings are actually held in churches, but rely on secularized language and practices, not scripture and liturgy. Nevertheless, Fincher suggests that piety still lingers in the background. At Remaining Men Together, when the protagonist is finally able to cry, choral music plays on the soundtrack, implying that, despite the secularized context, the weeping has a deeply spiritual quality, a connection reinforced by the main character’s use of evangelical terms to describe the experience. He says the groups make him feel “born again” and “resurrected.” The chemical burn scene connects this ambiguity and ambivalence back to the gender issue when Tyler says, “Our fathers were our models for God. If our fathers bailed, what does that say about God?” Tyler’s answer: “God does not like you. In all probability, he hates you.”

In other words, God is dead: long live Fight Club! In Tyler we trust…

As Fight Club evolves into the extremism of Project Mayhem, the main target becomes the institutions that support consumerism. Like a gang of giddy juvenile delinquents, Project Mayhem terrorizes various consumer enterprises—auto dealerships, coffee shop franchises, etc.—before setting their sights on the institutions that ultimately feed and profit from the modern obsession with fabricated happiness: the banking and credit industry. By blowing up the banks and wiping out everyone’s credit history, Project Mayhem thinks it’s liberating people from the great oppressor, the false religion of consumerism.

Fight Club is about an alienated person’s strange, disturbing search for identity and existential purpose. It utilizes archetypal elements to reflect on what it means to be both a male and a spiritually-hungry consumer in postmodern America. In doing so, the film suggests that changes in the way gender and religious values are now constructed can have potentially destructive repercussions. While the reasons for these changes are valid and noble, e.g. gender equality and scientific progress, Fight Club reminds viewers to pay attention to what is happening to those who once benefited from gender inequality and Christian definitions of power: men. The film is a warning: paradigm shifts in identity and social norms can create gaping psychological holes that the Home Shopping Network cannot fill. In a culture where power relations are constantly changing, dark and violent ideas can fester inside insecure minds and erupt with horrific consequences.