Once upon a time, in some out of the way corner of that universe which is dispersed into numberless twinkling solar systems, there was a star upon which clever beasts invented knowing. That was the most arrogant and mendacious minute of ‘world history,’ but nevertheless, it was only a minute. After nature had drawn a few breaths, the star cooled and congealed, and the clever beasts had to die.

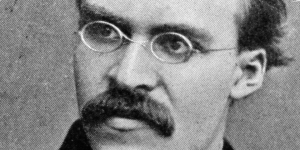

If you’re a fan, you might think this an excerpt from an H.P. Lovecraft story, one of his twisted tales about erudite, curious men who learn too much about the nature of reality and are either destroyed or deeply damaged by what they discover. But this is actually the opening to Nietzsche’s essay “On Truth and Lies in an Extra-moral Sense” (1873), a biting critique of the epistemological pretentiousness he finds running rampant through Western philosophy. Nietzsche is an iconoclastic philosopher, hammering away at venerated ideas, slashing through sacred assumptions. He gleefully turns traditional theories on their heads, challenging our beliefs, disturbing our values—an intellectual calling that has much in common with H.P. Lovecraft’s literary mission. His favorite theme is what he calls cosmic indifferentism. If Lovecraft has a philosophy, it is this: the universe was not created by a divine intelligence who infused it with an inherent purpose that is compatible with humanity’s most cherished existential desires. The cosmos is utterly indifferent to the human condition, and all of his horrific monsters are metaphors for this indifference.

Nietzsche and Lovecraft are both preoccupied with the crises this conundrum generates.

“What does man actually know about himself?” Nietzsche asks, “Does nature not conceal most things from him?” With an ironic tone meant to provoke his readers, he waxes prophetic: “And woe to that fatal curiosity which might one day have the power to peer out and down through a crack in the chamber of consciousness.” In Lovecraft’s “From Beyond” (1934) this ‘fatal curiosity’ is personified in the scientist Crawford Tillinghast. “What do we know of the world and the universe about us?” Tillinghast asks his friend, the story’s unnamed narrator. “Our means of receiving impressions are absurdly few, and our notions of surrounding objects infinitely narrow. We see things only as we are constructed to see them, and can gain no idea of their absolute nature.” His Promethean quest is to build a machine that lets humans transcend the inherent limitations of our innate perceptual apparatus, see beyond the veil of appearances, and experience reality in the raw. From a Nietzschean perspective, Tillinghast wants to undo the effect of a primitive but deceptively potent technology: language.

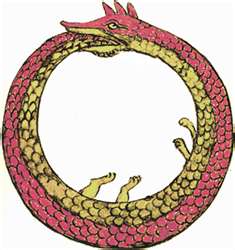

In “On Truth and Lie in an Extra-moral Sense,” Nietzsche says symbolic communication is the means by which we transform vivid, moment-to-moment impressions of reality into “less colorful, cooler concepts” that feel “solid, more universal, better known, and more human than the immediately perceived world.” We believe in universal, objective truths because, once filtered through our linguistic schema, the anomalies, exceptions, and border-cases have been marginalized, ignored, and repressed. What is left are generic conceptual properties through which we perceive and describe our experiences. “Truths are illusions,” Nietzsche argues, “which we have forgotten are illusions.” We use concepts to determine whether or not our perceptions, our beliefs, are true, but all concepts, all words, are “metaphors that have become worn out and have been drained of sensuous force, coins which have lost their embossing and are now considered as metal and no longer as coins.” [For more analysis of this theory of language, read my essay on the subject.]

Furthermore, this process happens unconsciously: the way our nervous system instinctually works guarantees that what we perceive consciously is a filtered picture, not reality in the raw. As a result, we overlook our own creative input and act as if some natural or supernatural authority ‘out there’ puts these words in our heads and compels us to believe in them. Lovecraft has a similar assessment. In “Supernatural Horror in Literature” (1927), his essay on the nature and merits of Gothic and weird storytelling, he says the kind of metaphoric thinking that leads to supernatural beliefs is “virtually permanent so far as the subconscious mind and inner instincts are concerned…there is an actual physiological fixation of the old instincts in our nervous tissue,” hence our innate propensity to perceive superhuman and supernatural causes when confronting the unknown. Nietzsche puts it like this: “All that we actually know about these laws of nature is what we ourselves bring to them…we produce these representations in and from ourselves with the same necessity with which the spider spins.” This, of course, applies to religious dogmas and theological speculations, too.

In “From Beyond,” Crawford Tillinghast wants to see “things which no breathing creature has yet seen…overleap time, space, and dimensions, and…peer to the bottom of creation.” The terror is in what slips through the rift and runs amok in this dimension. His scientific triumph quickly becomes a horrific nightmare, one that echoes Nietzsche’s caveat about attaining transgressive knowledge: “If but for an instant [humans] could escape from the prison walls” of belief, our “‘self consciousness’ would be immediately destroyed.”

Here in lies the source of our conundrum, the existential absurdity, the Scylla and Charybdis created by our inherent curiosity: we need to attain knowledge to better ensure our chances of fitting our ecological conditions and passing our genes along to the next generation, and yet, this very drive can bring about our own destruction. It’s not simply that we can unwittingly discover fatal forces. It’s when the pursuit of knowledge moves beyond seeking the information needed to survive and gets recast in terms of discovering values and laws that supposedly pertain to the nature of the cosmos itself. Nietzsche and Lovercraft agree this inevitably leads to existential despair because either we continue to confuse our anthropomorphic projections with the structure of reality itself, and keep wallowing in delusion and ignorance as a result, or we swallow the nihilistic pill and accept that we live in an indifferent cosmos that always manages to wriggle out of even our most clear-headed attempts to grasp and control it. So it’s a question of what’s worse: the terror of the unknown or the terror of the known?

Nietzsche is optimistic about the existential implications of this dilemma. There is a third option worth pursuing: in a godless, meaningless universe, we have poetic license to become superhuman creatures capable of creating the values and meanings we need and want. I don’t know if Lovecraft is confident enough in human potential to endorse Nietzsche’s remedy, though. If the words of Francis Thurston, the protagonist from his most influential story, “The Call of Cthulhu” (1928), are any indication of his beliefs, then Lovecraft doesn’t think our epistemological quest will turn out well:

“[S]ome day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality…we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.”